Gender Equality and WASH: Empowering Women and Girls Through Access and Agency

Recognizing World Water Week 2022

The connection between gender and water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) management is undeniable, yet this intersectionality remains poorly accounted for in measurement and program implementation.

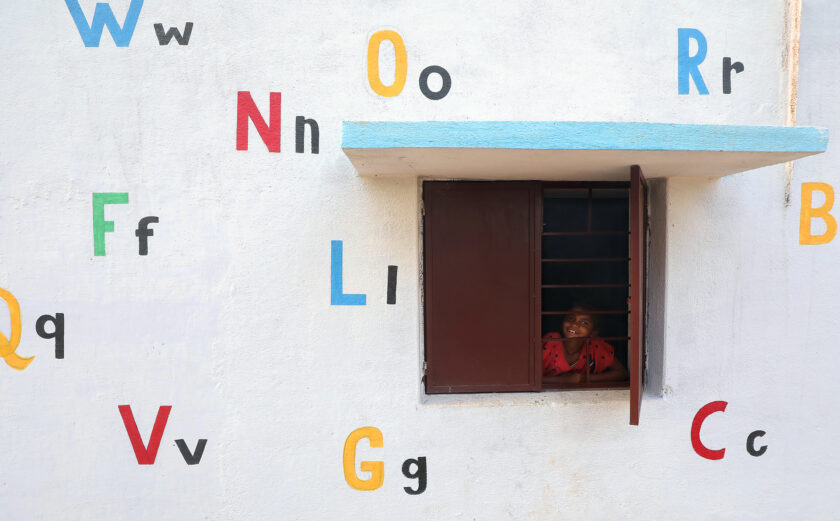

Women and girls traditionally bear the primary water management responsibility for cooking, cleaning, caretaking, and agriculture. Still, they lack proper access to WASH services and facilities to meet their needs related to menstruation, pregnancy, and caretaking. The lack of access to basic WASH infrastructure contributes to a disproportionate experience of poor health outcomes and risks related to WASH, such as physical strain and injury, gender-based violence, and psychosocial stress with missed educational, economic, and social opportunities.

Societal Stigmas in WASH Development

Most governmental bodies that develop WASH systems are run by men, most of whom are not living with a disability. This results in WASH service delivery being “insensitive to the needs of women and other SEGs [socially excluded groups] at both community and societal levels.”

Poverty, low awareness of social inclusion topics, and disproportionate access to education further inhibit the socioeconomic status and social mobility of women.

The International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health revealed that in the Oromia Region of Ethiopia, less than half of the households in the area have access to clean drinking water, 29% have access to private sanitation facilities, and only 14% have access to handwashing facilities with soap. Women, girls, and other socially excluded groups are also rarely consulted or engaged by local actors.

Due to limited WASH facilities, many women avoid urination by limiting their food and water intake. Female caretakers and girls involved in household activities experience an increased risk of WASH-related illness. Additionally, girls have higher levels of school absenteeism largely due to stigmas associated with menstruation which limit a student’s access to menstruation materials, sanitation and hygiene facilities, and sufficient water access.

When these basic needs go unmet, the women responsible for work, income generation, and community management cannot participate equally in society. According to UNICEF, more than half of the women in Bangladesh and two-thirds in Nepal said they did not participate in everyday activities while menstruating. Similarly, one in three women in Chad and the Central African Republic reported they felt they “missing out” while menstruating.

The Need for Women’s Agency in WASH Decision-Making

The Women’s Empowerment in Agriculture Index (WEAI) constitutes empowerment as agency and categorizes three types of agency.

- Intrinsic agency: Women develop a sense of “individual confidence and capacity, undoing the effects of internal oppression.”

- Instrumental agency: Women influence the nature of decision-making through negotiation.

- Collective agency: Women become aware of their own interests in relation to others to participate from a position of strength, influence, and cooperation to achieve a more significant impact than they could alone.

Empowerment is achieved by increasing one’s ability to resist and challenge systemic and internalized oppression. This opens access to decision-making processes and challenges negative social constructs.

By ensuring that women are participants in the decision-making processes that drive WASH development, the inequitable outcomes of WASH services can be avoided. Giving women instrumental and collective agency to build systems that support the health of all people could increase the level of intrinsic agency women experience in these communities by removing the barriers to living a healthy life.

With sustainable WASH outcomes, marginalized individuals may maximize the opportunities available to them and realize themselves “as having the capacity and the right to act and have influence.” Moreover, increased agency and access to WASH services allow women and girls to participate equally in society.

2022 U.S. Global Water Strategy

Women’s autonomy must be embraced, and their participation welcomed in the decision-making on WASH systems’ design, service availability, safety, and security. Moreover, WASH programs should be built on the demands and wishes of those who participate in them. Instead of a ‘top-down’ directive approach that encourages dependency, external actors should take a facilitative approach that requires conscious and sustained efforts and promotes confidence in the people directly impacted by the intervention. USAID’s “nothing about them, without them” rubric must be ingrained across policies and programs to empower local voices as a fundamental part of each mission’s success.