Conflict-Induced Hunger: Linking the War in Ukraine to the Global Food Insecurity Crisis

Currently, 50 million people worldwide face the risk of famine, a reality exacerbated by the war in Ukraine.

After lengthy negotiations, the Russia-Ukraine July grain deal—hailed as a ‘beacon of hope’—has since allowed 720,000 tons of Ukrainian wheat and other cereals that were previously stranded at port to be distributed to the global market. However, the deal faces serious complexities, limitations, and security concerns. A short timeline, compounded by shipping companies and insurers wary of drifting sea mines and a Russian missile strike on the port of Odesa less than 24 hours after the deal was signed, has undermined safety guarantees for ship crews.

Given the mounting global hunger crisis, the deal may have come too late. And as warned by the latest Hunger Hotspots Report by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and the World Food Programme (WFP), the number of those at risk of starvation is unprecedented.

Detailing the impact of the war in Ukraine on global food security

After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, disruptions to Ukrainian agricultural production and logistics decreased grain exports from 7 million to 2 million tons per month. Prior, grain exports were dependent on maritime shipping. However, Russia’s Black Sea blockade necessitated a hasty patchwork of overland and river routes—constrained by train and border capacity, fuel shortages, and technological differences in railways between Ukraine and Europe.

Russian soldiers have directly targeted agricultural infrastructure across Ukraine, including grain silos, food warehouses, railways, and ports, further impacting both production and distribution. Subsequently, conflict-induced high input prices, especially impactful due to Ukraine’s reliance on smallholder rural farmers, have harmed domestic agricultural production. In total, the decline in area harvested and limited access to inputs are expected to result in a 40% decline of cereal production this year. And earlier this summer, the U.S. informed 14 countries that they could be the recipients of allegedly stolen Ukrainian grain.

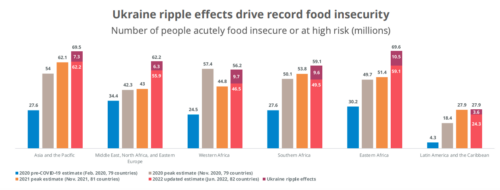

The conflict in Ukraine is widely considered a tipping point of the global food crisis—an arbiter rather than the sole executioner. Climate change, the COVID-19 pandemic, economic instability, supply chain issues, and extreme weather have drastically squeezed food supplies. In October 2021, food prices had already surpassed the prior December 2010 record.

The conflict struck a vulnerable point within an already delicate and highly concentrated global food system. Seven countries are the source of 86% of the world’s total grain exports. The Russian Federation and Ukraine were leading exporters of many agricultural products, including fertilizers, maize, wheat, and barley, and Ukraine’s grain alone fed 400 million people worldwide. Fifty countries rely on the two states for more than half of their wheat imports, many of which fall into the Least Developed Country (LDC) and Low-Income Food-Deficit Country (LIFDC) groups.

The decrease in exports resulting from the war drastically compounded pressure on global food availability, leading to inflation in food and other commodities. The crisis has triggered price increases of up to 30% for staple foods, and between January and April 2022, the FAO Food Price Index rose by 17%. For every percentage point increase in global food prices, 10 million more people are pushed into extreme poverty.

What is conflict-induced hunger, and how does its frame aid in our analysis of the Ukraine crisis?

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has exposed millions to hunger. Global leaders have been keen to highlight the link: in a recent U.N. Security Council debate, the head of WFP, David Beasley, called the failure by Russia to open ports in southern Ukraine, “a declaration of war on global food security [that] will result in famine, destabilization, and mass migration around the world.”

Conflict-induced hunger, a relatively new term with no single or set definition, is used to recognize the reality that armed conflict is one of the leading drivers of global hunger. Over 70% of people in crisis levels of food insecurity live in countries affected by conflict. From 2020 to 2021, the number of people facing acute hunger due to conflict rose by 40 million. In response, U.N. Security Council Resolutions 2417 and 2573 (passed in 2018 and 2021, respectively) not only identified the linkages of conflict to hunger but condemned the use of starvation as a method of warfare in violation of international humanitarian law (IHL).

Looking to the future

Despite recent increases in funding—G7 countries pledged an additional $4.5 billion for emergency global food assistance)—total global commitments to food assistance amount to less than one-third of the $46 billion in current total humanitarian food aid appeals worldwide.

Responding to the crisis, InterAction and its Member organizations have called on world leaders to take further urgent action. We encouraged donor governments to widen resources beyond the immediate victims of war and enumerated concrete steps to integrate a conflict-induced hunger and protection analysis within the global response.

More broadly, the weaponization of food as a strategy and outcome of violent conflict is not likely to disappear. Beyond emergency assistance, the international community must address root causes of food insecurity exacerbated by conflict and invest in diplomacy, humanitarian access, and the resilience and diversification of our global food systems.

The Russia-Ukraine war will shape base paradigms of conflict as we study conflict-induced hunger and its intersections with International Humanitarian Law. Our current definitions of the physical boundaries of victimhood, methods of violence, and the paths we take to mitigate and prevent harm must expand to fit our new reality.